Joe Loya stepped into a San Diego bank just before closing with his fedora pulled low, his trench coat brushing his pants and his eyes hidden behind dark sunglasses.

He approached a teller and slid a note under the glass.

The teller read it and froze. “We have a bomb. I have a gun. Give me the money!” it read. The teller hesitated. “Now!” he hissed.

Loya stuffed $4,500 into a fanny pack, ran a few blocks, hailed a taxi and disappeared.

And with that, his life as a bank robber in the late 1980s began. Within a one-year stretch, he robbed about two dozen banks across Southern California – netting a quarter-million dollars — without ever firing the .357 Magnum he kept tucked in his waistband.

“I’m not jumping over the counter. I’m not gonna shoot them. I’m not gonna pistol-whip them,” he told CNN. “I have to (be) persuasive enough with my rage to get them to do it.”

During the robberies, he switched up his look – a suit one day, shorts the next. Some days, he traded the fedora for a baseball cap. Other times, he wore layers of clothes and peeled them off as he fled. But the sunglasses stayed on.

Investigators, mistaking his dark hair and olive skin for a Middle Eastern person, nicknamed him the “Beirut Bandit.”

But Loya, a private-school educated, Mexican-American who loved Russian history and science fiction, was not easily pigeonholed.

And before he started robbing banks, he’d once stabbed his father, an evangelical minister, with a steak knife in retaliation for years of physical abuse.

Betrayed by a girlfriend, Loya was arrested in May 1989 while waiting for her on the UCLA campus. He was 27.

He pleaded guilty to three robberies — police couldn’t conclusively tie him to the others — and served seven years in prison before his release in July 1996.

Loya has spent the last three decades confronting his criminal past. He wrote a memoir, “The Man Who Outgrew His Prison Cell,” and is the subject of a new podcast, “Get the Money and Run,” bringing his story to a new generation.

As part of his journey, he’s gone back into prisons to teach inmates to own their stories and use them for positive change. He’s also spent hours asking himself: Where did it begin? What led him to a life of crime?

He’s embraced every aspect of his messy life, violence and all. But don’t call his a redemption story.

“I think redemption is only part of the story. Only one,” he said. “To ascribe only one theme is to flatten me as a character, deny my human complexity.”

His childhood was shaped by grief, rage and religion

Loya’s father was a Southern Baptist minister. At the family’s home in East Los Angeles, religion shaped every aspect of their lives, he said.

As a boy, Loya would belt out the children’s hymn, “Jesus Loves Me, This I Know,” on cue for family and strangers alike. The first time he watched a movie about the crucifixion of Jesus, he broke down in tears.

Loya’s parents got married at 16, and his mother recorded her firstborn’s milestones in a baby book. One entry captured young Joe’s fiery nature: He has a temper. I guess he takes after his father.

Father and son would later fulfill that prophecy in unimaginable ways.

Loya’s childhood, he said, alternated between moments of joy and dread. Sometimes his father would get down on all fours and pretend to be a horse as Joe and his younger brother gleefully climbed onto his back.

But the lightness and laughter could vanish quickly. Joe Loya Sr. demanded perfection and used violence to get it, his son said.

“I had to memorize my multiplication tables. My dad would do this thing where he wanted us to be the smartest kids in the class because we were scholarship kids and we were the brown kids,” Loya said. “He wanted us to be better and smarter than the other kids.”

His father gave him math tests after work and whooped him with a belt for any questions missed, he said.

At the time, Loya’s mother was dying of kidney disease. The pain of slowly watching his mother deteriorate, along with his fear and resentment of his father, festered quietly, he said.

“As my dad was beating me and I was taking each blow, there’s a different energy that builds up inside of you … the animosity, the negativity, that stuff. It changes your molecules, rearranges you and gives you power,” he said. “I was getting stronger. I was not getting weaker.”

His mother died when he was 9, leaving Joe and his brother without a protector. The abuse escalated, he said.

Loya’s father, 80, is in poor health and was unavailable to speak with CNN. But in the podcast and in previous interviews, he has confessed to beating his two children.

One night when Joe was 16, everything changed. After an especially vicious beating, he said he grabbed a steak knife from the kitchen and stabbed his father in the neck.

“He started screaming, ‘Oh, you killed me, you killed me!’” Loya said.

His father had a transformational moment as well.

“I kept saying give it (knife) to me, I’m not gonna hurt you anymore,” Loya Sr. said in the podcast. “And then it hit me — ‘He didn’t stab you — you made him stab you. You treated him that way. We’re here because of you …’

“It was my moment of clarity,” he said, his voice cracking with emotion. “I thought of his mother. I let her down. And I swore then I would change.”

His children were briefly placed in foster care. But Loya had finally flipped the script on his dad. He said he felt like David after toppling Goliath, like he’d finally broken free from his abuse.

He also learned that violence could give him control.

No longer eager to please his father, Loya’s connection to religion started unraveling. He felt strong, empowered.

He started engaging in petty crimes – stealing cars, falsifying his time sheet at the Pasadena restaurant where he worked as a cook, and defrauding friends and members of his dad’s congregation, he said.

Then he learned about Mexican bandit and revolutionary leader Pancho Villa, who in the early 1900s robbed banks, trains and the wealthy across northern Mexico and the southwestern US.

“I was like, you know, I’m going to do that,” he said. “I’m going to rob a bunch of banks.”

After he counted his stolen stack of bills in a motel following his first bank robbery, he was hooked.

“Nearly $4,500 felt glorious,” he said. “It was like, I don’t have to be a petty criminal ever again. I never have to defraud anybody. I get to be honorable now, except for this one bank robber thing.”

Loya took his new criminal career seriously, scouting out locations near highways for quick getaways. Sometimes he robbed a bank on foot or hopped into a taxi, slipping away as everyone searched for a getaway car.

On other days, he’d use his Mazda RX-7. Sometimes he’d target several banks in a day, he said. His biggest haul was about $33,000 from a federal savings bank in Tustin, California. That was in January 1989, according to court records.

Three months later, the FBI finally identified him after an armored car driver spotted his license plate as he fled a bank robbery in Camarillo, California.

The FBI reached out to Loya’s girlfriend, warning her she could be prosecuted as an accomplice because of the money she got from him – unless she helped bring him down.

“Good healthy advice. I have never begrudged her,” Loya said.

She told the FBI that Loya was planning to drop by UCLA, where she was a student, to give her some money before fleeing to Mexico like his hero, Villa.

On May 13, 1989, as he sipped a cappuccino on a bench waiting for his girlfriend on the UCLA campus, a young man approached and said, “Joe Loya?” He instinctively answered yes. The man turned out to be one of several FBI agents scattered across campus, searching for him.

At first, prison didn’t change him. Loya said he kept up his criminal activity behind bars, including smuggling drugs and assaulting other inmates. He believed violence would earn him respect in prison, too.

He spent two years in solitary confinement at a federal penitentiary in Lompoc, California, after stabbing another inmate. Forced into long periods of silence, he reflected on his turbulent life. And he began exchanging letters with his father.

More than four decades later, Loya makes no apologies about his heists. “Banks are insured. They’re fine. They make a lot of money off people,” he said.

But one aspect of his robberies bothers him to this day.

“The thing that haunted me, that gave me shame, that made me feel guilty, was robbing the tellers — the trauma that I put them through,” he said.

He’s never attempted to locate the tellers, whose names were listed in court documents. And he doesn’t plan to, he said.

“I believe that I did hurt people in some ways worse than if I punched them or kicked them when they were on their knees,” he said.

Asking for a meeting with his victims is like robbing them all over again, he said.

“I ambushed them with my emotional incontinence,” he said. “I deposited in front of them all my rage, my confusion, desperation, resentment. I just dumped it all in front of them. And I got money for it, while they had to deal with the aftermath.”

Because of his income from his book and podcast, some critics have accused him of capitalizing on his criminal past. But no amount of money can make up for his personal trauma since his mother died, he said.

“To profit is to make more than what you spent to create the thing of value,” he said. “So no, there has been no profit earned back yet.”

Loya, 63, now lives in Berkeley, California, where he works as a writer and a podcaster. For the divorced father of a teenage daughter, his violent past is never far behind. He’s in therapy to deal with it.

One thing has brought him joy over the years, he said: working with former and current inmates.

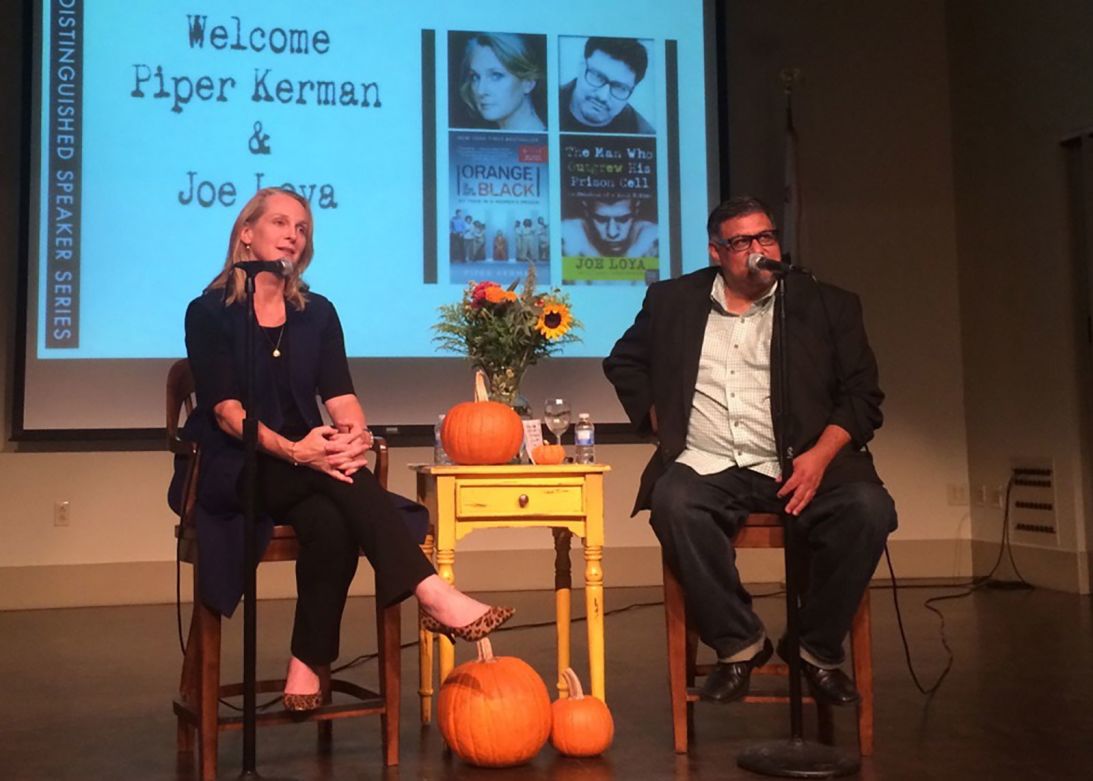

He’s collaborated with author Piper Kerman, whose “Orange is the New Black” memoir inspired the Netflix series by the same name – to share human stories behind prison walls.

Loya sent Kerman a letter while she was serving a year in prison for drug trafficking and money laundering, and the two have been friends ever since.

“He was the only one person who was writing to me who had themselves been incarcerated,” she said. “He knew how difficult life in prison can be and how important writing is to keep your brain and your heart alive.”

Over the years, the pair have hosted workshops and writing classes in state prisons and elsewhere to highlight the power of storytelling.

“It’s a strange thing when you talk about an experience as traumatic and shameful and dangerous as being incarcerated. But Joe does it with a great sense of humor,” Kerman told CNN. “And when it’s clear a person has done that work, it’s easier for them to forge that sense of connection with a broad array of people. And that’s certainly true for Joe.”

Rosario Zatarain, who was in prison for drugs and Armed robbery, also tries to live by that.

She met Loya in June 2008 when he spoke at the California Institution for Women as part of the Chino facility’s drug rehabilitation program.

“I saw him and thought, this guy’s not a bank robber. He looks like a bank teller,” she said.

She was taken aback by how easily he shared his story. She stayed in touch with him, hoping to learn how to come to terms with parts of her life she’d struggled to accept.

Zatarain was paroled a year later, and Loya became her mentor as she navigated post-prison life. She felt insecure about her criminal past and struggled to get a job, fearful that her tattoos and background would lead people to judge her, she said.

Now, as a drug and alcohol counselor, Zatarain proudly showcases her tattoos and uses her past battle with meth to connect with others. Thanks to Loya, she’s not just owned her past — she’s rewritten it, she said.

“In Joe, I saw somebody who used his downfall … what everybody else judges you for — as his superpower,” she said. “Joe helped me see that people like us belong in society, too. He would be like, ‘No we don’t want to be good enough in their eyes. We want to be good enough in our eyes, and that’s all that matters.’”

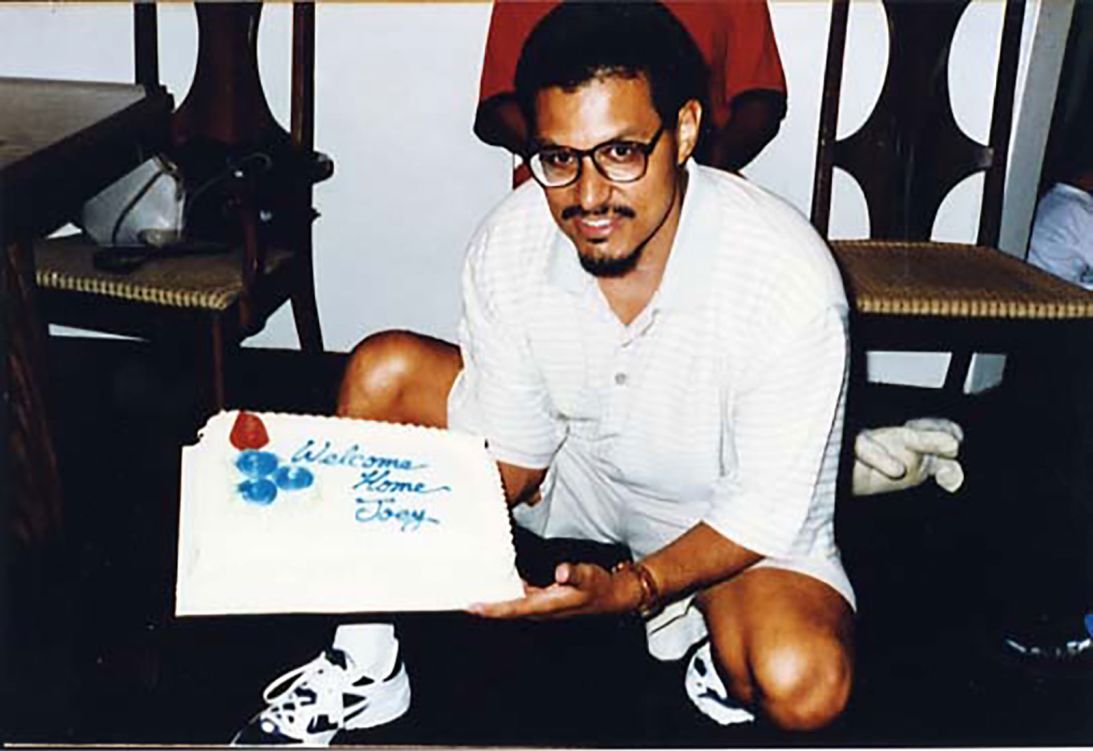

The day Loya walked out of prison, his father greeted him with a cake glazed in thick white frosting. “Welcome Home Joey,” it read in blue letters.

Determined to start afresh, the two men opened up about their fears and learned how shattered they both were by the loss of Loya’s mother. The scar on his dad’s neck from the stabbing became a symbol of their shared trauma.

“We’ve spent years repairing the damage I caused — rebuilding the family I nearly destroyed. It’s been slow, deliberate work. But we’ve done it with love. And that’s the story I carry forward — one I tell with honesty and care,” the younger Loya said.

Before his father’s recent illness, they visited prisons together to share their story of forgiveness. They dug deep into their anger and pain, and how it took over their lives.

“For me to change, I had to develop a lot of compassion for myself and for him. And then I started reviewing my life. Why did I do this?” the younger Loya said. He said he found an answer.

“I was wounded, I was scared, I was insecure. I didn’t feel safe,” he said.

If Loya could talk to his younger self, he said he wouldn’t bother warning him to stay away from crime. He knew it was wrong, he said, but he considered it an escape from a violent father. Instead, he’d tell young Joe to lean into his passion for writing and use it to make sense of his complicated life, he said.

“When someone’s hurting, you don’t just tell them to stop,” he said. “You meet them with compassion and help them find a way through.”

Loya is now working on another memoir in the form of letters to his 19-year-old daughter, Matilde.

Given his past, fatherhood didn’t come easy.

“I did not want to have a child (at first), because I feared I’d be like my dad,” he said.

His daughter has given him another chance to rewrite his story. And this time, he said, the violence ends with him.