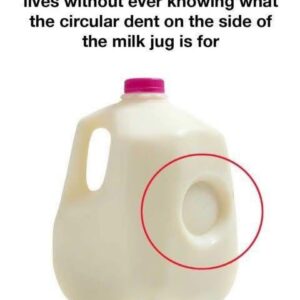

Mother Elizabeth Gonzales, father Alexander Gonzales Sr. and sister Angel Gonzales (left to right) during a vigil for Gonzales Jr. in 2021 (photo by John Anderson)

“I have shots fired,” repeated ex-APD officer Gabriel Gutierrez on Tuesday, June 24. As far as what Gutierrez actually meant by that phrase, attorneys in Robert Pitman’s federal court seemed divided.

Four and a half years ago, off-duty officer Gabriel Gutierrez shot Alex Gonzales Jr. and his girlfriend Jessica Arellano while the officer was on his way back from the gym, dressed in his personal clothes and driving his personal vehicle. While Gutierrez claims Gonzales had a gun pointed at his head and that he could not see Arellano when he fired into the car, the plaintiffs allege that his version of events is unlikely.

Gonzales’ parents, Alex Gonzales Sr. and Elizabeth Gonzales, brought the present suit against not only Gutierrez, but also the city of Austin for consistently failing to discipline officers who shoot people.

After testimony about both Gutierrez’s actions and the APD investigation that followed, Pitman tossed out the portion of the case against the city. Assistant City Attorney Gray Laird argued that the plaintiffs didn’t demonstrate that Gutierrez’s decision to shoot was influenced by the knowledge that he wouldn’t face consequences for it. While the police department is off the hook, the trial continues for Gutierrez.

Several disputed facts sat at the heart of this case. Critically for the case against Gutierrez: whether or not Alex Gonzales pointed a gun at Gutierrez’s head. The first three witnesses brought by the plaintiffs gave expert testimony, weaving together the events on the night of Gonzales’ death on January 5, 2021.

For the city, the key issue was whether their negligence in investigating police shootings caused Gonzales’ death. Steve Chancellor, investigation review expert, said key aspects of APD’s investigation into Gonzales’ death were done poorly or not at all. Chancellor highlighted the lack of a shooting incident reconstruction, which he considers “critical” and usually “automatic” in an investigation of this sort. He said that Gutierrez should have been interviewed the night of, and should have been pressed on his testimony with the facts in later interviews. He said that lab notes and other documents were missing from investigation reports and that important facts like a loose bullet found in Gutierrez’s car were never mentioned. Based on his extensive review, Chancellor said that APD conducted an “inadequate investigation.”

The plaintiffs then introduced a forensic pathologist and an audiovisual analyst who revealed that other details from the investigation and Gutierrez’s story were inaccurate or incomplete. While the city claimed in its reports that eight shots were fired, forensic analysis of video evidence shows the correct number is seven. While Gutierrez claimed that he reached for his gun only after seeing Gonzales point his own gun, just 2.7 seconds passed between the moment the cars pulled up next to each other and when Gutierrez started shooting. The first three witnesses made the plaintiff’s case that key details in the Special Investigations Unit and Internal Affairs investigations were missing, unlikely, or just plain incorrect.

Then, the plaintiffs called Gutierrez to the stand. Attorney Donald Puckett pressed Gutierrez on his testimony, pointing out discrepancies in his version of events compared to the physical evidence and calling into question the ex-APD officer’s credibility.

A central conflict in Gutierrez’s testimony resulted from confusion around the phrase “I have shots fired.” When Gutierrez called 911 after shooting Gonzales and Arellano, he told the dispatcher that he was an off-duty APD officer, that he had shots fired, and that the other person involved was still holding a gun.

“I realized this was a one-sided situation.” – Eyewitness Campbell Green

The plaintiffs’ team played the 911 call for Gutierrez, stopping every few seconds to ask questions. Puckett asked Gutierrez if he may have misled the dispatcher, not having mentioned that only he had shot someone and that he couldn’t actually see Gonzales holding a gun after initially shooting him. Gutierrez said no, that under the circumstances, he relayed the information to the best of his ability, given the limited time available and his state of shock.

While Gutierrez agreed that his understanding of shots fired was ambiguous – meaning it could indicate shots aimed at him from someone else or fired by himself – he repeated that he had told the 911 operator accurate information and that his statement was clear.

Puckett closed his examination with a series of pointed questions. Are you willing to acknowledge that you have not told the full truth? Are you willing to acknowledge that your 911 call was misleading? Gutierrez responded “no” to each question.

Albert Lopez, Gutierrez’s defense attorney, cross-examined him. Lopez established that no one disciplined Gutierrez at any point during his time at APD and that he had never used lethal force before. He also reiterated Gutierrez’s full belief that Gonzales pointed a gun at his face and that he made a reasonable choice in his split-second decision to shoot into Gonzales’ car.

The plaintiffs next brought eyewitness Campbell Green to the stand. Green, a resident at the apartments across from where the incident occurred, testified that he saw Gonzales sitting in his car with his hands at 10 and 2 while Officer Gutierrez shouted “drop your gun” again and again. He testified at that moment, “I realized this was a one-sided situation,” and felt as though “this was unethical, this was wrong.”

The first responding officer to Gutierrez’s call, who fatally shot Gonzales, Luis Serrato, testified next. Serrato said, based on the information given by Gutierrez on the 911 call and in person once he arrived, that he believed he was responding to a domestic violence situation and needed to protect Arellano from Gonzales. He testified that he came to this conclusion based on the information provided by Gutierrez, including Gutierrez’s omission that he had shot Gonzales in the head.

Serrato additionally testified that the Austin Police Department trains officers to use the phrase “shots fired” to indicate that an individual who is not an officer has shot munitions. He clarified, however, that hearing “shots fired” from a 911 caller does not necessarily indicate the police’s understanding of the phrase.

Lopez then cross-examined Serrato, asking whether hearing “shots fired” vs. “shots taken” would have changed his decision to shoot. Serrato said no. Lopez also asked the officer if he blamed Gutierrez for what happened. Serrato responded, “No, sir, I don’t.”

Jeffrey Noble – a use-of-force expert for the plaintiffs who also testified in the trial over the death of George Floyd – walked jurors through a series of hypotheticals representing various versions of the events on January 5, 2021. Noble said that even if the jury believes all the facts as claimed by Gutierrez, the off-duty officer should have sped his car up so as not to be in front of a gun rather than raise his own and start shooting.

The decision not to discipline Gutierrez and the lack of explanation for that decision add to a “culture of impunity” that Noble said the Austin Police Department has struggled with. The expert witness said that longstanding deficiencies with Internal Affairs, one of two internal investigative bodies for police conduct, enabled a culture permissive to unconstitutional uses of force.

Jurors heard directly from APD’s oversight bodies. The plaintiffs called members of the Office of Police Oversight and the Community Police Review Commission, who testified that both groups reviewed the materials from APD’s investigations and both recommended indefinite suspension for Gutierrez. Then-Chief Joseph Chacon, however, decided against their recommendation, declining to take disciplinary action.

Detective Steven McCormick, now sergeant, at the Special Investigations Unit, testified that he did not record body-cam footage the night of the incident and also did not record body-cam footage 10 days later when he searched the victim’s car. He said that their team did not forensically analyze the audio to confirm how many shots occurred and had to prompt others, which he found unusual, in SIU to write reports about their investigation.

Despite these facts, McCormick said that he considers this investigation to be thorough, unbiased, and a fair reflection of the majority of SIU investigations.

Look for more coverage online and in next week’s issue.